I was twelve when The Phantom menace came out. Sitting in that theater, I was instantly blown away by the fast-paced, acrobatic lightsaber choreographies of Nick Gillard. I was smitten with this fresh take on Jedi abilities, and I am ashamed to say that I then looked on the original duels of Peter Diamond with disappointment and perhaps even a touch of scorn. To my younger self, this new style was the coolest thing I’d ever seen, and the old duels had lost their luster in the face of such riveting stuntwork. (I was also twelve.)

Perhaps even into some of my adult years I never quite got over that “meh” opinion of the original trilogy lightsaber duels.

But now I want to rectify that misperception.

Since the release of the prequels, many have explained the difference between Gillard’s and Diamond’s work by focusing on the timeline and condition of the combatants. These explanations are compelling, so I won’t focus on that particular point. Rather, I want to take another look at the OT lightsaber duels with a fresh perspective.

Seeing the Duels Differently

Almost a year ago I began practicing kendō with a local group. And as I learn more about kendō and proper technique, I find that I am seeing the lightsaber duels of the Star Wars films in a new way.

But before I jump in, here’s a bit about kendō for context: Kendō is the Japanese sport of swordfighting. Each combatant, or kenshi, wields a bamboo sword called a shinai. The goal is to strike the opponent’s head, wrist, body, or throat with proper technique, follow-through, and vocalization. Both contenders will get hit (sometimes a lot), but between closely matched opponents, it can be quite difficult to perform a clean technique worthy of a point. The matches will often last for minutes for this reason.

Relating Kendō to the Original Trilogy

Kendō is about technique, speed, and precision. It focuses on economy of movement. That means you won’t see spinning, aerial leaps, or sword twirling. These kinds of movements are generally impractical, taking too much time and energy to use effectively. The moment you start doing those in kendō will also be the moment you lose. When I watch the OT duels with this in mind, this economy of movement is what I see. There are a few spins here and there, and Luke flips maybe twice, (all arguably guided by the Force) but mostly the attacks are direct and purposeful. What I once saw as lackluster fight choreography I now see as intelligent swordplay. The prequel fights are fast and flashy, showing each opponent searching for an opening in the other’s defense. But it seems to me that OT fights show the combatants trying to make openings in the other’s defense. Here, just as in kendō, it appears that one’s best defense is a good offense.

Bladelock

I used to think it was farcical – that moment when two combatants lock blades for a prolonged moment, ensuing in a momentary battle of strength. And honestly, in most unstaged swordfights, that would be the case (most engagements will last seconds, not minutes). However, in the context of a protracted engagement, the situation is not necessarily as contrived as I once thought.

Both kenshi and Force users end up in prolonged matches – In kendō because it’s difficult to score points, and in SW because Force users can counter attacks for extended periods of time.

In these matches, bladelock is actually quite likely. When both opponents move in to attack and are unable to complete their techniques, they get stuck inside each other’s defenses, sometimes resulting ing locking blades, or tsuba zeriai (meaning “hilt to hilt”). Though to be fair, most cases of bladelock in the OT are brief and further apart than tsuba zeriai in kendō.

In the OT we also see – particularly in the Obi-Wan/Vader duel – moments where the combatants take jabs, taps, or momentarily lock blades in an almost playful manner. This happens all the time in kendō. One opponent will try to create an opening by batting or nudging the other’s weapon out of the way, simultaneously trying to distract or psych out him/her. Having been on the receiving end of this, let me just say it’s really annoying. It can be an effective tactic when used well.

Which brings me to my final observation.

The Battle of Wills

The swordplay in kendō seeks to defeat the opponent in any of three ways: 1) Kill the opponent. 2) Disable the opponent (i.e. cutting the sword hand) 3) Break the opponent’s will to fight.

With that in mind, I see that third method at work in the OT more than ever before. In tense moments, such as locking or tapping blades, each opponent may be trying to physically push the other off balance, break the other’s guard, etc. But tandem to that physical struggle is a mental one.

Speaking from personal experience, even the briefest of moments can break your resolve in a fight. One moment of hesitation, one fleeting mistake, one moment of being even slightly bested, and you can lose mentally before you ever lose physically.

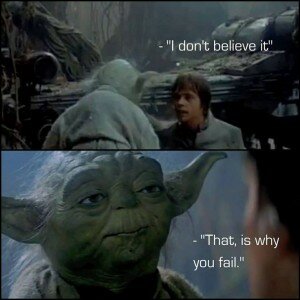

It’s given me a whole new understanding of the words “Do, or do not. There is no try.” The moment you go from ‘doing’ to ‘trying’ in kendō is the moment you forfeit the fight. And I think Master Yoda would agree that is also true of wielding a lightsaber.

With this understanding, I feel like I can finally appreciate the OT lighstaber duels for what they really are: a clever coalescence of swordplay and psychological combat.

And I can happily say that now I enjoy watching them more than ever ^_^ leave a comment below.

Picture sources:

networka.com, Starwarsanon.wordpress.com, kendodc.com, japaoemfoco.com, thejourneytoextraordinary.wordpress.com

The Cantina Cast

The wretched hive your Jedi Master warned you about!

Follow

Follow